RIP The Idea(l) of The West

lsraeI shows us what we are, and exposes in a harsh light what we are not.

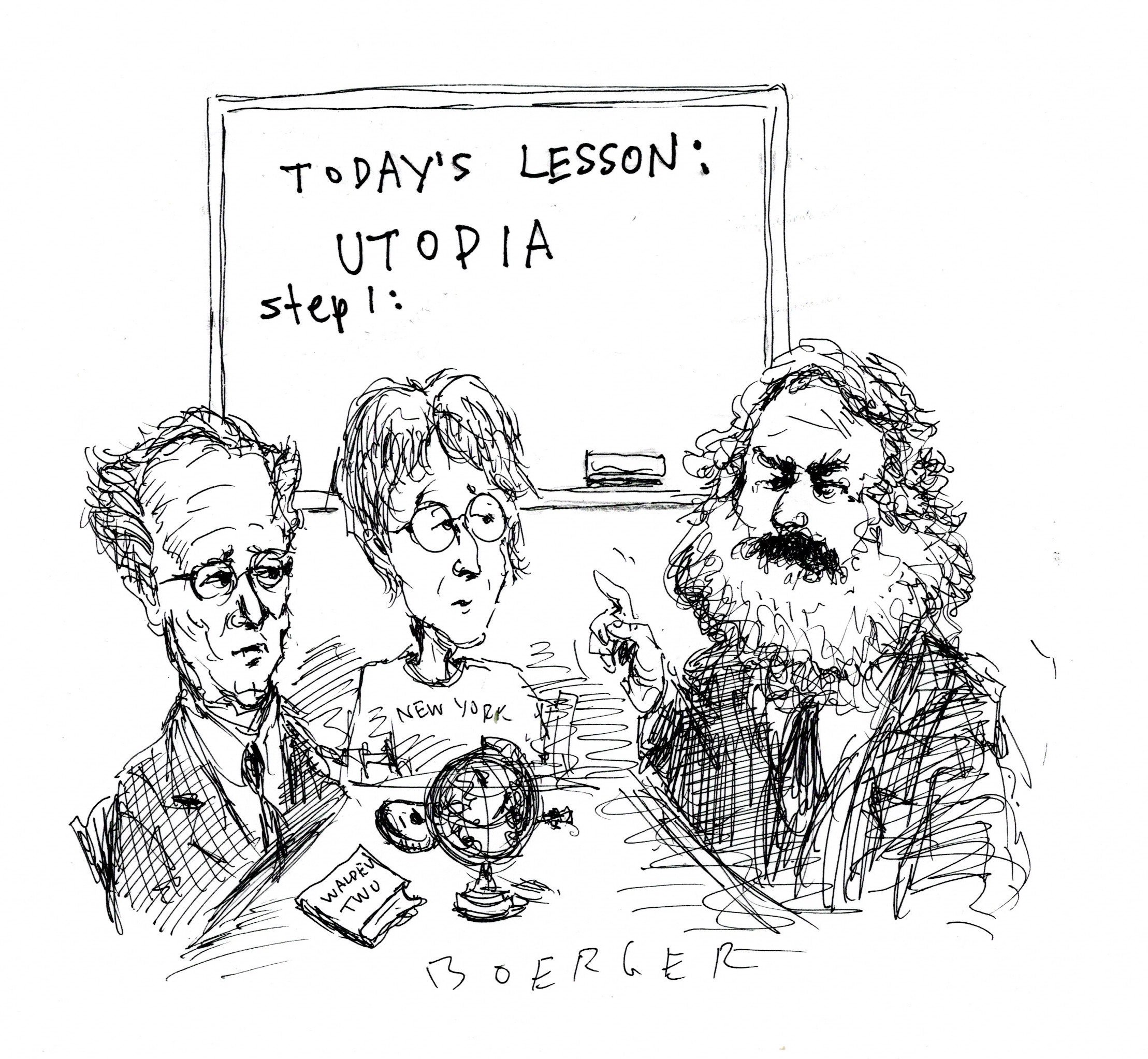

In 1992, Francis Fukuyama published his it-made-sense-when-I-was-stoned NYT bestseller, 'The End of History' in which he argued that history itself had essentially come to an end with the fall of the Soviet Union. He argued that 'western values' had prevailed and would surely go on to encompass the entire world; a triumphant victory not only for 'the West' but for all mankind which would from that point forward concede that these 'western values' of democracy, capitalism and technological supremacy were better than any other form of society that had ever been tried, such as monarchy, papacy, communism, Maoism, Islamism, etc. The long march of history had led inevitably and inexorably to these 'western values' for which we had Socrates, Aristotle, and, grudgingly, Plato to thank.

Ah, Fukuyama, what a pompous dope.

The truth is that his notion of the superiority of 'western values' has always been a hard sell. Witch burnings, the slave trade, France's Reign of Terror were signs enough that something was off with Fukuyama's views, but Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Mai Lai and Bhopal should have knocked the notion out of his noggin for good. Yet, people love myths which paint them as the good guy, and so the idea of 'triumphant western values' continued to have some currency.

Until Israel. Until a genocidal maniac received a standing ovation from both Democrats and Republicans in the US Capitol. Until pathetic clowns purporting to lead the US, Germany, the UK and France all rushed to condemn Iran for committing the crime of being attacked by lsraeI. 'lsraeI is facing an existential threat!' they parrot, excusing an unprovoked attack on a sovereign nation, while ignoring the fact that it is indeed the Palestinian people who truly face an existential threat, FROM lsraeI. The truth is plain to see. These 'western values' are.... valueless.

Not worth the paper they are printed on.

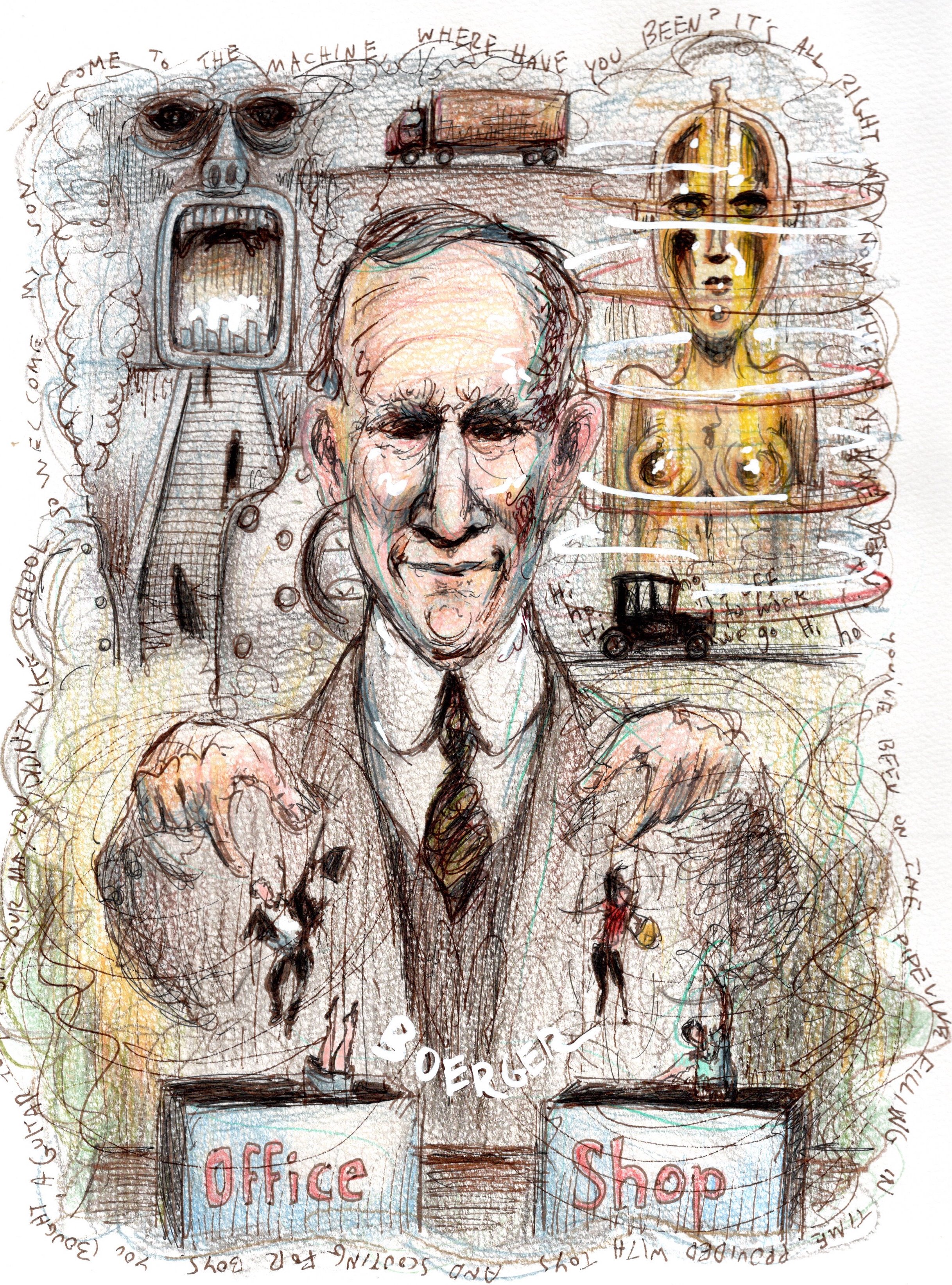

The reality that power - specifically the power to impose one’s will on others - was not merely incidental to the 'triumph' of the West but was in fact its sin qua non, has always been a rather imposing elephant in the room.

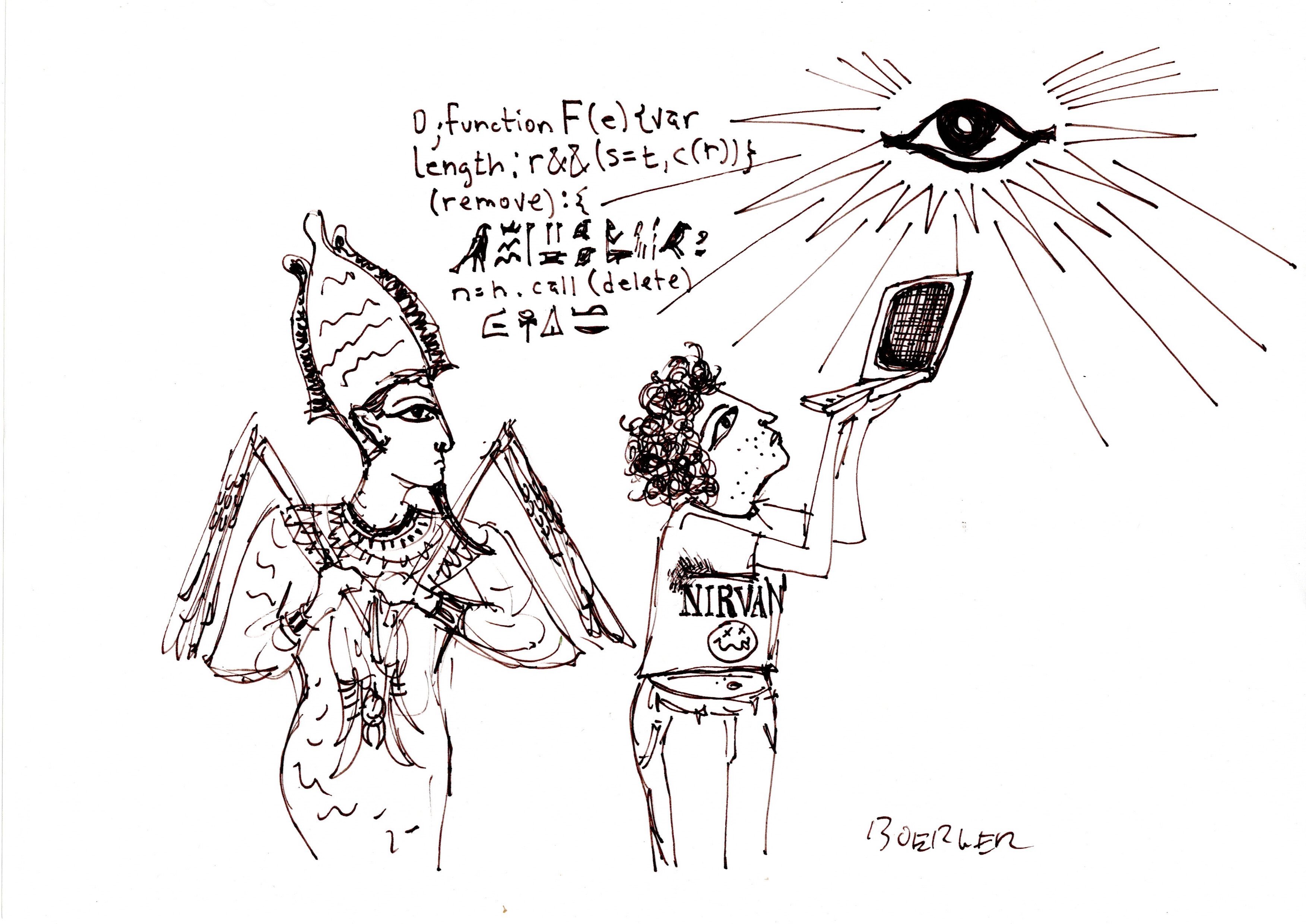

Secularists could argue that it was the precise and impeccably organized thinking of the ancient Athenian philosophers that stood as the bedrock of the West, while religious folk could argue that it was Christ (who became blue eyed and Western) and latter Christian scholars like Thomas Aquinas who added a revolutionary morality that combined with Athenian philosophy to make it an unstoppable force.

But now, how hollow that all seems. It was the ships. It was the guns. It was the technological superiority of the West, not its philosophical or moral superiority - or its 'democratic ideals' - that enabled it to prevail over rivals.

The precision of Aristotlean thinking, combined with the the Christianization of the world's most powerful empire, led to the development of Gutenberg's printing press (first used as a Bible press), which led to the European Enlightenment. It all seems to be about the triumph of ideas, does it not? Well, no. This precise thinking and information access yielded the physical and tangible aspects of Western power that account for its 'triumph': steam power, TNT, the internal combustion engine, flight, jet fuel, the unlocking of the atom, and so on.

The West did not persuade, it imposed. This is the brute reality that Western triumphalists either choose to ignore or embrace with a sick child's glee.

And this brings us to lsraeI. What the Zionist state is doing today is not different from what Western powers have done for centuries. From the Age of Exploration onwards, it has always been Western military might, brought about by its technology - NOT the courage of its soldiers or the advanced thinking of its generals - that resulted in the vast empires of Spain, Portugal, England and Holland; France, Belgium and Italy in Africa, the United States in its conquest of the indigenous tribes, and so on.

It was collusion of many of these same Western powers that produced the state of lsrael, a colonialist enterprise that followed a playbook dating back at least as far as the conquistadors. Where is the so-called superiority of Western 'values' in this? European nations treated European Jews so badly that they finally decided to give them a 'homeland' that just so happened to be somebody else's home. What did England, France and the United States care about that little detail? They had made careers out of invading other peoples' homes and slaughtering them. Is it any wonder that should be their game plan with the Zionist project?

There was no chance that the morals they had supposedly picked up from Aristotle and Jesus were going to impel them to make a reconciliation with their Jews in good faith and in the spirit of repentance. It is to laugh.

No, these colonial monstrosities did the only thing they really know how to do well; they created yet another oppressive colonialist state (a proxy governorship, if we're being honest) in the heart of that troublesome land of Arabia, that decidedly un-Western realm whose people they had warred with for centuries. lsraeI was the West's way of preventing a pan-Arab nation that hated the West while possessing massive amounts of the West's new gold - petroleum - from becoming a rival that could possibly challenge their hegemony. From its inception, lsraeI was every bit as much about keeping the Arabs down as it was about uplifting Jews.

And so we can finally bury the idea of the 'triumph' of Western values, morals, philosophy yada yada, in the most unceremonious way at our disposal. It would all be hysterical - a Monty Python skit brought to life - if it weren't so heartbreakingly tragic. In the 20th century European colonialists made a deal with their ancient victims - European Jews - to victimize non-European people (the Palestinians) by brutally stealing land from them that supposedly had been 'promised' to the Jews - by a SKY GOD no less - centuries before Socrates and Aristotle had ever breathed air. Hardly 'the West' as it likes to see itself.

It's all as phony as the blue eyed Jesus.

Truly a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.

The End

In 1992, Francis Fukuyama published his it-made-sense-when-I-was-stoned NYT bestseller, 'The End of History' in which he argued that history itself had essentially come to an end with the fall of the Soviet Union. He argued that 'western values' had prevailed and would surely go on to encompass the entire world; a triumphant victory not only for 'the West' but for all mankind which would from that point forward concede that these 'western values' of democracy, capitalism and technological supremacy were better than any other form of society that had ever been tried, such as monarchy, papacy, communism, Maoism, Islamism, etc. The long march of history had led inevitably and inexorably to these 'western values' for which we had Socrates, Aristotle, and, grudgingly, Plato to thank.

Ah, Fukuyama, what a pompous dope.

The truth is that his notion of the superiority of 'western values' has always been a hard sell. Witch burnings, the slave trade, France's Reign of Terror were signs enough that something was off with Fukuyama's views, but Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Mai Lai and Bhopal should have knocked the notion out of his noggin for good. Yet, people love myths which paint them as the good guy, and so the idea of 'triumphant western values' continued to have some currency.

Until Israel. Until a genocidal maniac received a standing ovation from both Democrats and Republicans in the US Capitol. Until pathetic clowns purporting to lead the US, Germany, the UK and France all rushed to condemn Iran for committing the crime of being attacked by lsraeI. 'lsraeI is facing an existential threat!' they parrot, excusing an unprovoked attack on a sovereign nation, while ignoring the fact that it is indeed the Palestinian people who truly face an existential threat, FROM lsraeI. The truth is plain to see. These 'western values' are.... valueless.

Not worth the paper they are printed on.

The reality that power - specifically the power to impose one’s will on others - was not merely incidental to the 'triumph' of the West but was in fact its sin qua non, has always been a rather imposing elephant in the room.

Secularists could argue that it was the precise and impeccably organized thinking of the ancient Athenian philosophers that stood as the bedrock of the West, while religious folk could argue that it was Christ (who became blue eyed and Western) and latter Christian scholars like Thomas Aquinas who added a revolutionary morality that combined with Athenian philosophy to make it an unstoppable force.

But now, how hollow that all seems. It was the ships. It was the guns. It was the technological superiority of the West, not its philosophical or moral superiority - or its 'democratic ideals' - that enabled it to prevail over rivals.

The precision of Aristotlean thinking, combined with the the Christianization of the world's most powerful empire, led to the development of Gutenberg's printing press (first used as a Bible press), which led to the European Enlightenment. It all seems to be about the triumph of ideas, does it not? Well, no. This precise thinking and information access yielded the physical and tangible aspects of Western power that account for its 'triumph': steam power, TNT, the internal combustion engine, flight, jet fuel, the unlocking of the atom, and so on.

The West did not persuade, it imposed. This is the brute reality that Western triumphalists either choose to ignore or embrace with a sick child's glee.

And this brings us to lsraeI. What the Zionist state is doing today is not different from what Western powers have done for centuries. From the Age of Exploration onwards, it has always been Western military might, brought about by its technology - NOT the courage of its soldiers or the advanced thinking of its generals - that resulted in the vast empires of Spain, Portugal, England and Holland; France, Belgium and Italy in Africa, the United States in its conquest of the indigenous tribes, and so on.

It was collusion of many of these same Western powers that produced the state of lsrael, a colonialist enterprise that followed a playbook dating back at least as far as the conquistadors. Where is the so-called superiority of Western 'values' in this? European nations treated European Jews so badly that they finally decided to give them a 'homeland' that just so happened to be somebody else's home. What did England, France and the United States care about that little detail? They had made careers out of invading other peoples' homes and slaughtering them. Is it any wonder that should be their game plan with the Zionist project?

There was no chance that the morals they had supposedly picked up from Aristotle and Jesus were going to impel them to make a reconciliation with their Jews in good faith and in the spirit of repentance. It is to laugh.

No, these colonial monstrosities did the only thing they really know how to do well; they created yet another oppressive colonialist state (a proxy governorship, if we're being honest) in the heart of that troublesome land of Arabia, that decidedly un-Western realm whose people they had warred with for centuries. lsraeI was the West's way of preventing a pan-Arab nation that hated the West while possessing massive amounts of the West's new gold - petroleum - from becoming a rival that could possibly challenge their hegemony. From its inception, lsraeI was every bit as much about keeping the Arabs down as it was about uplifting Jews.

And so we can finally bury the idea of the 'triumph' of Western values, morals, philosophy yada yada, in the most unceremonious way at our disposal. It would all be hysterical - a Monty Python skit brought to life - if it weren't so heartbreakingly tragic. In the 20th century European colonialists made a deal with their ancient victims - European Jews - to victimize non-European people (the Palestinians) by brutally stealing land from them that supposedly had been 'promised' to the Jews - by a SKY GOD no less - centuries before Socrates and Aristotle had ever breathed air. Hardly 'the West' as it likes to see itself.

It's all as phony as the blue eyed Jesus.

Truly a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.

The End

BXI Builingual System started translating.

BXI Builingual System started translating.